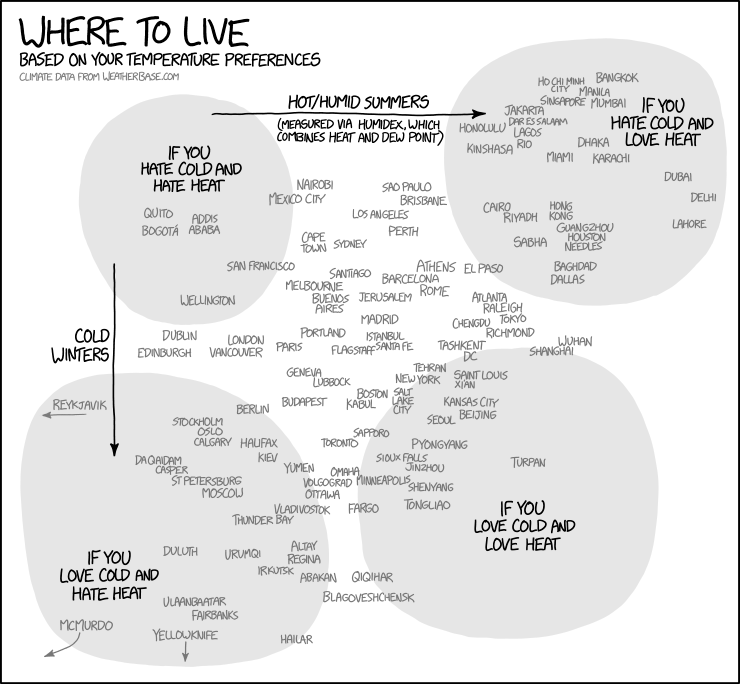

First xkcd for a while I don't think works. I have been to Riyadh and Hong Kong in the summer. I find it hard to believe anyone who loves one of their climates would even like the other. Dubai+Delhi seems dubious too though I have no first hand experience there.

I felt like I needed to stipulate right in the headline that this is not "fake news," because, well, it may be difficult to believe that this is where we are.

Following Betsy DeVos' confirmation as Secretary of Education, Republican Representative from Kentucky Thomas Massie introduced legislation to abolish the federal Department of Education.

Really.

The legislation, H.R. 899, is one sentence long: "The Department of Education shall terminate on December 31, 2018."

Really.

It already has at least seven co-sponsors: Rep. Justin Amash (R-MI), Rep. Andy Biggs (R-AZ), Rep. Jason Chaffetz (R-UT), Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-FL), Rep. Jody Hice (R-GA), Rep. Walter Jones (R-NC), and Rep. Raul Labrador (R-ID).

Really.

In a press release, which you can read in its entirety at Massie's House website, Massie says: "Neither Congress nor the President, through his appointees, has the constitutional authority to dictate how and what our children must learn."

Really.

And: "Unelected bureaucrats in Washington, D.C. should not be in charge of our children's intellectual and moral development."

Really.

And: "It is time that we get the feds out of the classroom, and terminate the Department of Education."

Really.

You might imagine that Massie's legislation is some sort of critical commentary on the selection of DeVos, but that would be wrong. Because DeVos almost certainly shares his opinion about the department she was just confirmed to run.

After all, as I have been observing since the day Trump selected her, DeVos' only qualification is her willingness to destroy the Department of Education.

She was chosen specifically to be the perfect partner for Trump, who has said he wants to break up the "government-run education monopoly," and for Pence, who has been destroying public education in Indiana for quite some time, and for Bannon, whose exploitation of ignorance is significantly aided by subverting public education.

The GOP has spent decades shouting at poor and/or marginalized people to pull themselves up by their bootstraps, and now they want to take away their best opportunity to access a pair of boots.

Following Betsy DeVos' confirmation as Secretary of Education, Republican Representative from Kentucky Thomas Massie introduced legislation to abolish the federal Department of Education.

Really.

The legislation, H.R. 899, is one sentence long: "The Department of Education shall terminate on December 31, 2018."

Really.

It already has at least seven co-sponsors: Rep. Justin Amash (R-MI), Rep. Andy Biggs (R-AZ), Rep. Jason Chaffetz (R-UT), Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-FL), Rep. Jody Hice (R-GA), Rep. Walter Jones (R-NC), and Rep. Raul Labrador (R-ID).

Really.

In a press release, which you can read in its entirety at Massie's House website, Massie says: "Neither Congress nor the President, through his appointees, has the constitutional authority to dictate how and what our children must learn."

Really.

And: "Unelected bureaucrats in Washington, D.C. should not be in charge of our children's intellectual and moral development."

Really.

And: "It is time that we get the feds out of the classroom, and terminate the Department of Education."

Really.

You might imagine that Massie's legislation is some sort of critical commentary on the selection of DeVos, but that would be wrong. Because DeVos almost certainly shares his opinion about the department she was just confirmed to run.

After all, as I have been observing since the day Trump selected her, DeVos' only qualification is her willingness to destroy the Department of Education.

She was chosen specifically to be the perfect partner for Trump, who has said he wants to break up the "government-run education monopoly," and for Pence, who has been destroying public education in Indiana for quite some time, and for Bannon, whose exploitation of ignorance is significantly aided by subverting public education.

The GOP has spent decades shouting at poor and/or marginalized people to pull themselves up by their bootstraps, and now they want to take away their best opportunity to access a pair of boots.

Next Page of Stories